The recent pre-print of (Wainberg et al. 2017) examined the TWAS approach for prioritizing target genes in GWAS studies. The work has relevance to a broad class of methods for “post-GWAS” analysis and spurred interesting discussions. As an author of one of these methods (Gusev et al. 2016), I thought it would be useful to talk about what TWAS is doing; why; and how it fits into our current understanding of complex traits.

UPDATE: The authors respond here with thoughtful points and useful additional context. Please read the whole thing, but I specifically want to echo their point that understanding how well TWAS (and other methods) prioritize causal genes is a critical question right now. I think one way to move toward an answer is by establishing clear metrics for what we consider a successful prioritization (ideally metrics that are agnostic of QTL evidence) and systematically evaluating the performance of all commonly used approaches (including manual curation).

What is TWAS?

TWAS is a test for significant association between the cis component of gene expression and the GWAS trait. It is part of a broad class of approaches that identify relationships between QTL and GWAS to find target genes. These approaches have many applications: risk prediction; pathway enrichment; causal inference between traits; drug repurposing; identifying disease-associated epigenetic features; and gene prioritization. In their pre-print, WEA explore the application of TWAS to causal gene prioritization in a GWAS of Crohn’s disease and LDL cholesterol. First, they observe loci where TWAS identifies an association at the presumed causal gene, but also at other genes. Second, they switch to less appropriate tissues and find that TWAS often no longer observes an association for the presumed causal gene but observes associations to other genes. They conclude that the approach is therefore “invalid” for finding causal genes. This conclusion is driven by a misinterpretation of TWAS as a causal inference test rather than a test for association. Subsequent claims of “vulnerability”, “false discovery”, and “instability” stem from this misinterpretation. TWAS is neither vulnerable nor invulnerable to discovering non-causal genes because it is not a test for causality. Just as a GWAS study identifies significantly associated non-causal SNPs which need to be fine-mapped, so too a TWAS study will find significantly associated non-causal genes. WEA do not present any cases of false associations, which would be a true vulnerability for TWAS. Although WEA focus on our TWAS/FUSION method because it’s so easy to use [kidding!], they conclude that these vulnerabilities apply to many methods including SMR, PrediXcan, Sherlock, coloc, QTLMatch, eCAVIAR, enloc, RTC – which I’ll generally refer here to as QTL/GWAS methods.

What are QTL/GWAS methods doing?

The goal of these methods is to estimate properties of the genetic relationship between gene expression and GWAS trait. They fall into two broad categories:

- TWAS/FUSION, PrediXcan/MetaXcan, SMR: A test for significant genetic correlation between cis expression and GWAS. A helpful intuition is that when the cis expression of a gene is driven entirely by a single eQTL $i$, the resulting test statistic will be equal to the raw GWAS association of $i$. (Note: approximately for SMR because it incorporates the uncertainty on the eQTL … but SMR also restricts to eQTLs with very low uncertainty)

- coloc, eCAVIAR, enloc: An estimator of the posterior probability of colocalization, where colocalization is defined as one (or more) shared causal variants between the expression and GWAS. In the case of a single eQTL $i$, this probability will approach 1.0 only if the probability of the causal configuration containing $i$ for the GWAS is also high. In this example, TWAS association is necessary but not sufficient for colocalization. A secondary difference is that colocalization maxes out at a posterior of 1.0, regardless of the underlying effect-size, whereas TWAS also captures the strength of the genetic association. In this way the two approaches are complementary.

To my knowledge, none of these methods claim to perform causal gene discovery (see footnote). Causal inference is challenging. It is especially challenging when you have a single snapshot of the phenotypes you’re interested in and a relatively small number of independent variants. So these approaches estimate support for less stringent gene-disease relationships: how strongly are the variants associated with expression also associated with the trait? what’s the probability that the same causal variants are shared between expression and the trait?

Why do we care about these genes if they are not causal?

While the QTL/GWAS methods do not perform causal inference, we still believe they are useful in prioritizing genes for experimental follow-up relative to other GWAS approaches. This is challenging to quantify because there are so few known examples of true-positive causal genes, and even fewer known examples of true-negatives. One nice aspect of the WEA analysis is that they tried to find such genes in the literature and then asked whether they show up as TWAS hits. In fact, most of the known genes DO came up as significant TWAS associations when evaluated in the expected tissue (though, keep in mind that many of these genes were initially identified precisely because they had eQTLs) and the number of null genes with associations is relatively low (assuming they are all truly null). I would humbly recommend the alternative title “TWAS is actually pretty good at identifying association for causal genes”. [UPDATE: The authors point out in their response that they only evaluated those genes that were TWAS associations and therefore did not assess sensitivity]. That said, there are now multiple examples in the literature that these methods are doing something useful:

- In (Gusev et al. 2016) we showed that genes identified by a height TWAS were more correlated with measured height (out of sample) than the nearest gene or the best eQTL gene for a GWAS hit. That TWAS genes are more strongly associated with phenotype suggests that they are more likely to be causal than nearest genes.

- Similarly, in (Gusev et al. 2016) we showed that a TWAS-based risk prediction model was more strongly correlated with schizophrenia than one based on corresponding top SNPs.

- In (Mancuso et al. 2017) we showed that the TWAS genes are more significantly associated than the nearest gene, have stronger eQTL effects at the index SNP, and yielded more consistent cross-trait genetic correlations than SNPs in the locus.

- (Fromer et al. 2016) used a combination of Sherlock/COLOC to select three genes for experimental validation in zebrafish and demonstrated that altering expression had a causal effect on neurodevelopment.

- (Barbeira et al. 2017) showed that genes causally implicated in rare recessive diseases by ClinVar were more strongly associated with related common diseases by PrediXcan. Retrospectively, the genes identified by PrediXcan are thus more likely to be causal for rare disease than un-selected genes.

- (Marigorta et al. 2017) showed that overall expression of COLOC-selected genes is much more strongly associated with disease and is predictive of future complications (in contrast to genetic risk scores). This is a beautiful study and, in my opinion, the clearest evidence that QTL/GWAS methods prioritize genes with a causal effect on trait and have prognostic value.

When does TWAS have more power than GWAS?

A lot of the work we did in (Gusev et al. 2016) was about understanding when the TWAS model does and does not increase power to identify new associations (again, the focus was on discovery and not fine-mapping the causal gene). So to summarize:

- TWAS will do better when multiple variants associated with expression are also associated with the disease. The increase in power comes from aggregating those effects into a single test. This includes the case when there is a single shared causal variant but it is partially tagged by multiple variants in the GWAS.

- TWAS will do worse when the genetic effect on expression is independent of the trait, in which case TWAS becomes just an arbitrary transformation of the local SNPs.

We specifically showed that “novel” genes identified by a TWAS of lipids (genes that did not overlap genome-wide significant SNPs) replicated better in a larger lipid GWAS study than non-TWAS loci at the same level of significance. We again demonstrated this for the educational attainment phenotype in (Mancuso et al. 2017) where 4 out of 4 “novel” TWAS genes found in an early GWAS had genome-wide significant SNPs in a larger, more recent GWAS. I like this result a lot and I think it’s a gold-standard for showing that an association method improves power in real data. But I didn’t include it in the above list because it could still be consistent with non-causal TWAS associations (if, for example, eQTLs and causal variants tend to colocalize for uninteresting reasons such as proximity to promoters/enhancers, high minor allele frequency, high LD, etc).

In hindsight I think we focused a bit too much on novel locus discovery given the many other cool things people are now doing with TWAS, but there continue to be instances where TWAS yields target genes that GWAS cannot find (Gao et al. 2017; Hoffman et al. 2017).

Can we get closer to causality?

Language aside, WEA are correct to point out that TWAS can identify genes that do not appear to be causal in instances where GWAS SNPs regulate multiple genes. As with GWAS, this motivates fine-mapping methods that probabilistically reduce the list of putative target genes without losing the causal gene. WEA are pessimistic about this research direction: “Is it possible, despite the limitations of TWAS, to somehow perform statistical fine-mapping and determine the causal gene or genes? We believe that it is not, even in principle.” But I disagree: if the genetically driven causal expression effect is observed in the tested reference panel then it will have a genetic association with the disease and (in principle) be identifiable by TWAS. Together with my colleague Nick Mancuso, we recently presented such a fine-mapping approach, which identifies credible sets of genes that contain the causal gene at pre-defined level (e.g. 90%), and others are working on similar ideas. As in GWAS fine-mapping, there is an assumption that the causal effect is observed in the study, but the results from WEA in LDL and Crohn’s suggest that this is true enough in real data to be worth investigating.

How important is the right cell-type?

The other observation WEA describe is the phenomenon of “instability”, where TWAS associations are observed in one reference tissue but not in other reference tissues. The meaning of “instability” is fuzzy (well, negatively fuzzy), but such a TWAS association is no more unstable than an eQTL that is significant in some tissues and not others. Indeed, in (Gusev et al. 2016) we showed that genes with significant predictors can differ between studies even in the same tissue (Table S2). We believed that this was primarily due to QC/environmental differences between studies because predictors translated well across studies (Table S3). More recent work by (Liu et al. 2017) using data from GTEx estimated a mean genetic correlation of 0.75 across 11 tissues. In other words, the optimal predictor built in the “wrong” tissue will, on average, have a correlation of 0.75 to the optimal predictor in the right tissue.

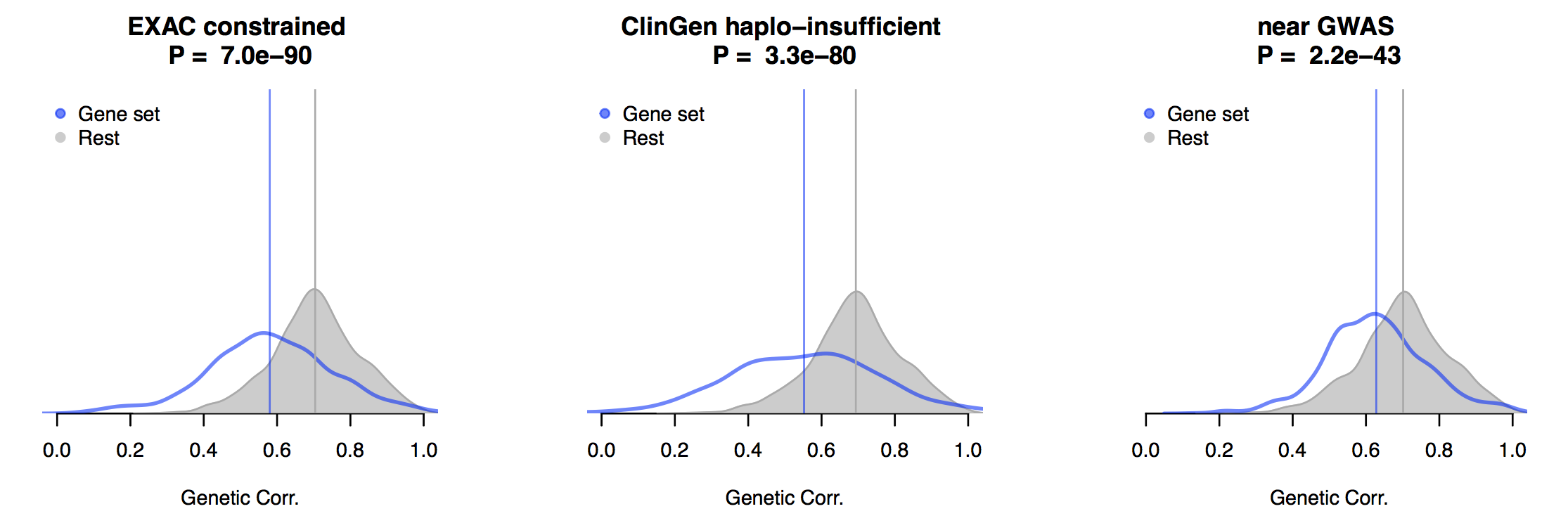

An interesting caveat demonstrated in the latest (GTEx Consortium et al. 2017) paper is that disease associated variants are enriched at tissue-specific eQTLs. However, even when we restrict the GTEx genetic correlation analysis to gene sets that are constrained in ExAC/ClinGen or near known GWAS hits, the mean genetic correlation across pairs of tissues remains high (albeit significantly lower than other genes), as shown in this (unpublished) figure across all pairs of GTEx tissues:

While it is important to be reminded of tissue differences, the cross-tissue genetic similarity is high enough to justify using all of the data that is available to us. The amount of genetic sharing is much lower, however, for trans/distal effects on expression, which brings us to a big question:

Does TWAS matter in an omnigenic age?

The recent perspective from (Boyle, Li, and Pritchard 2017) proposed a model of disease where tens-of-thousands of variants have minor (and biologically uninteresting) effects on disease, which cascade through a small set of “core” genes. Recent expression studies have shown that nearly every gene has a cis-eQTL in some tissue, so, optimistically, TWAS can help prioritize the core genes at large-effect GWAS loci.

But let’s imagine an extreme case where core genes are not under cis regulation. Does TWAS provide any benefits? My answer is “No, but wait”. Under this architecture TWAS would identify thousands of cis-regulated non-core genes, which provide no deep biological meaning when interrogated experimentally. This is the premise of futility some folks see in the omnigenic model. But wait! As expression studies increase in size they will have power to predict the full component of expression rather than just cis effects. For core genes, TWAS performed on these genome-wide components will aggregate the thousands of individually miniscule effects that are mediated by non-core genes. These genome-wide associations between expression and trait should be highly significant and robust. With sufficient sample size, causal inference tests across the hundreds/thousands of variants that hit core genes could lend further support to the underlying association.

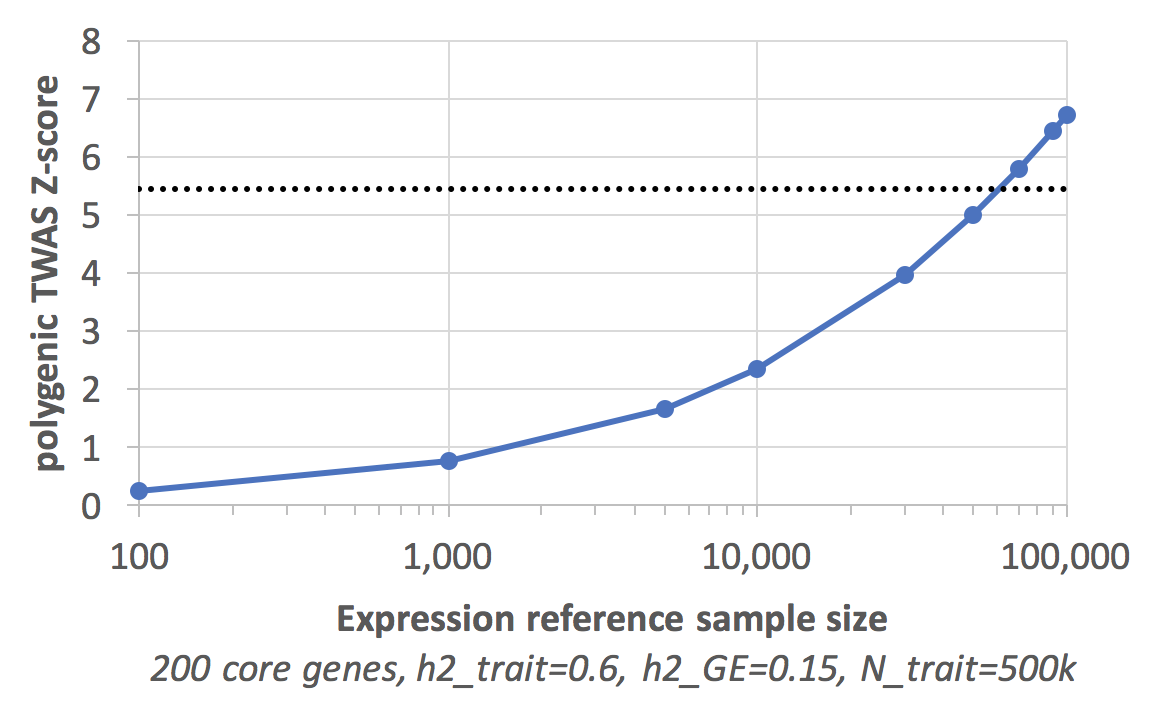

How practical is genomewide prediction of expression? Let’s do some simple math. Assume a trait with 500k genotyped individuals and SNP-heritability=0.60, 200 core genes and core gene expression SNP-heritability=0.15. Assuming heritability is uniformly distributed across each core gene and a very simple polygenic predictor of expression from (Daetwyler, Villanueva, and Woolliams 2008) we can ask how significant the resulting TWAS association would be as a function of the training size:

The dashed line is genome-wide significance, which is overkill for this analysis, but even for that cutoff all it takes is 70,000 individuals with measured expression. For comparison, GEO currently contains 1.2M human samples. Multiple studies are gearing up for whole-genome sequencing of 100,000 samples, with costs comparable to transcriptomics. It is, at most, a matter of years before we start to have an answer.

Thanks to Bogdan Pasaniuc for helpful comments

Footnote. Statements on causality from (Gusev et al. 2016):

- “We developed a new approach to identify genes whose expression is significantly associated to complex traits in individuals without directly measured expression levels (Methods) … Our approach can be conceptualized as a test for significant cis-genetic correlation between expression and trait (see Results).”

- “Our proposed method shares conceptual similarities with 2-sample Mendelian randomization approaches that aim to identify causal relations between traits using genetic variation predictions as a randomizer. However, while Mendelian randomization is intended to quantify the total causal effect, our method has the less strict goal of identifying significant associations.”

- “An alternative confounder arises from independent effects on phenotype and expression at the same SNP/tag (Figure 2G, Methods). Such instances could be indistinguishable from the desired causal model (Methods) without analyzing individual-level data, though we believe they are still biologically interesting cases of co-localization.”

References

- Wainberg, Michael, Nasa Sinnott-Armstrong, David Knowles, David Golan, Raili Ermel, Arno Ruusalepp, Thomas Quertermous, et al. 2017. “Vulnerabilities Of Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies.” BioRxiv. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. doi:10.1101/206961.

- Gusev, Alexander, Arthur Ko, Huwenbo Shi, Gaurav Bhatia, Wonil Chung, Brenda W J H Penninx, Rick Jansen, et al. 2016. “Integrative Approaches for Large-Scale Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies.” Nature Genetics 48 (3): 245–52. doi:10.1038/ng.3506.

- Gusev, Alexander, Nick Mancuso, Hilary K Finucane, Yakir Reshef, Lingyun Song, Alexias Safi, Edwin Oh, et al. 2016. “Transcriptome-Wide Association Study of Schizophrenia and Chromatin Activity Yields Mechanistic Disease Insights.” BioRxiv. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. doi:10.1101/067355.

- Mancuso, Nicholas, Huwenbo Shi, Pagé Goddard, Gleb Kichaev, Alexander Gusev, and Bogdan Pasaniuc. 2017. “Integrating Gene Expression With Summary Association Statistics to Identify Genes Associated with 30 Complex Traits.” American Journal of Human Genetics 100 (3): 473–87. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.01.031.

- Fromer, Menachem, Panos Roussos, Solveig K Sieberts, Jessica S Johnson, David H Kavanagh, Thanneer M Perumal, Douglas M Ruderfer, et al. 2016. “Gene Expression Elucidates Functional Impact of Polygenic Risk for Schizophrenia.” Nature Neuroscience 19 (11): 1442–53. doi:10.1038/nn.4399.

- Barbeira, Alvaro N., Scott P. Dickinson, Jason M. Torres, Rodrigo Bonazzola, Jiamao Zheng, Eric S. Torstenson, Heather E. Wheeler, et al. 2017. “Exploring The Phenotypic Consequences of Tissue Specific Gene Expression Variation Inferred from GWAS Summary Statistics.” BioRxiv. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. doi:10.1101/045260.

- Marigorta, Urko M, Lee A Denson, Jeffrey S Hyams, Kajari Mondal, Jarod Prince, Thomas D Walters, Anne Griffiths, et al. 2017. “Transcriptional Risk Scores Link GWAS to EQTLs and Predict Complications in Crohn’s Disease.” Nature Genetics 49 (10): 1517–21. doi:10.1038/ng.3936.

- Gao, Guimin, Brandon L Pierce, Olufunmilayo I Olopade, Hae Kyung Im, and Dezheng Huo. 2017. “Trans-Ethnic Predicted Expression Genome-Wide Association Analysis Identifies a Gene for Estrogen Receptor-Negative Breast Cancer.” PLoS Genetics 13 (9): e1006727. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006727.

- Hoffman, Joshua D, Rebecca E Graff, Nima C Emami, Caroline G Tai, Michael N Passarelli, Donglei Hu, Scott Huntsman, et al. 2017. “Cis-EQTL-Based Trans-Ethnic Meta-Analysis Reveals Novel Genes Associated with Breast Cancer Risk.” PLoS Genetics 13 (3): e1006690. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006690.

- Liu, Xuanyao, Hilary K Finucane, Alexander Gusev, Gaurav Bhatia, Steven Gazal, Luke O’Connor, Brendan Bulik-Sullivan, et al. 2017. “Functional Architectures Of Local and Distal Regulation of Gene Expression in Multiple Human Tissues.” American Journal of Human Genetics 100 (4): 605–16. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.03.002.

- GTEx Consortium, Data Analysis &Coordinating Center (LDACC)—Analysis Working Group Laboratory, Statistical Methods groups—Analysis Working Group, Enhancing GTEx (eGTEx) groups, NIH Common Fund, NIH/NCI, NIH/NHGRI, et al. 2017. “Genetic Effects on Gene Expression across Human Tissues.” Nature 550 (7675): 204–13. doi:10.1038/nature24277.

- Boyle, Evan A, Yang I Li, and Jonathan K Pritchard. 2017. “An Expanded View Of Complex Traits: From Polygenic to Omnigenic.” Cell 169 (7): 1177–86. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.038.

- Daetwyler, Hans D, Beatriz Villanueva, and John A Woolliams. 2008. “Accuracy Of Predicting the Genetic Risk of Disease Using a Genome-Wide Approach.” PloS One 3 (10): e3395. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003395.