A few years back I saw a talk by Chris Cotsapas drawing a comparison between performing genomewide association studies (GWAS) and putting together a parts list before figuring out how to fix a broken car. This analogy contextualizes the role of GWAS as necessary and crucial, but also highlights where the real payoff is - using the parts list to identify specific mechanisms. Since then, GWAS has identified thousands of parts, and in the past year we have started to see how those parts fit into the larger complex disease machine. Two recent studies - one from last month looking at schizophrenia and one from last year looking at obesity - start with GWAS loci and end with specific causal mechanisms. Both studies are clearly the culmination of much hard work and offer uniquely valuable insights. Here, I wanted to focus on aspects that are generalizable.

Ideally, we would design an algorithm that takes all available biological features and spits out very high posteriors on causality at these loci. Perhaps the algorithm would even discard those features that are irrelevant. Is such an algorithm feasible? Is there a recipe for inferring causality? To start answering these questions, I’ve summarized the structure of these two studies in the same way one would write a recipe for a cookbook. I’ve made some notes at the end on things that struck me, but I would be very interested in hearing alternative theories as well as examples from other diseases.

Obesity : FTO/IRX

Smemo et al. “Obesity-associated variants within FTO form long-range functional connections with IRX3” 2014 Nature

This paper used the 3D chromatin structure to identify a functional connection between the well-studied FTO locus for obesity and distal gene IRX3; identified enhancers that modulate IRX3; and showed that Irx3-deficient mice have significant body-weight differences.

Claussnitzer et al. “FTO Obesity Variant Circuitry and Adipocyte Browning in Humans” 2015 NEJM

This paper builds on the previous model to further disentangle the mechanism: a specific causal variant disrupts a repressor motif, the corresponding transcription factors de-represseses an enhancer, this leads to doubling of IRX3/IRX5 expression, and creates a developmental shift in adipocytes. Multiple biological assays were used to validate each step of this mechanism, including knockdown and CRISPR editing in human cells (this validation is the meat of the paper but I won’t focus on it here).

- Perform large-scale GWAS. The strongest genome wide association for BMI lies in introns 1 and 2 of the FTO gene. Focus on this locus.

- Use epigenetic annotations from 127 cell-types (the ROADMAP project) to predict the cell-type most likely to be causal. Identify unusually long enhancer in adipocyte progenitors. Measure association between risk haplotype and enhancer activity (2.4x higher) to confirm tissue-specificity.

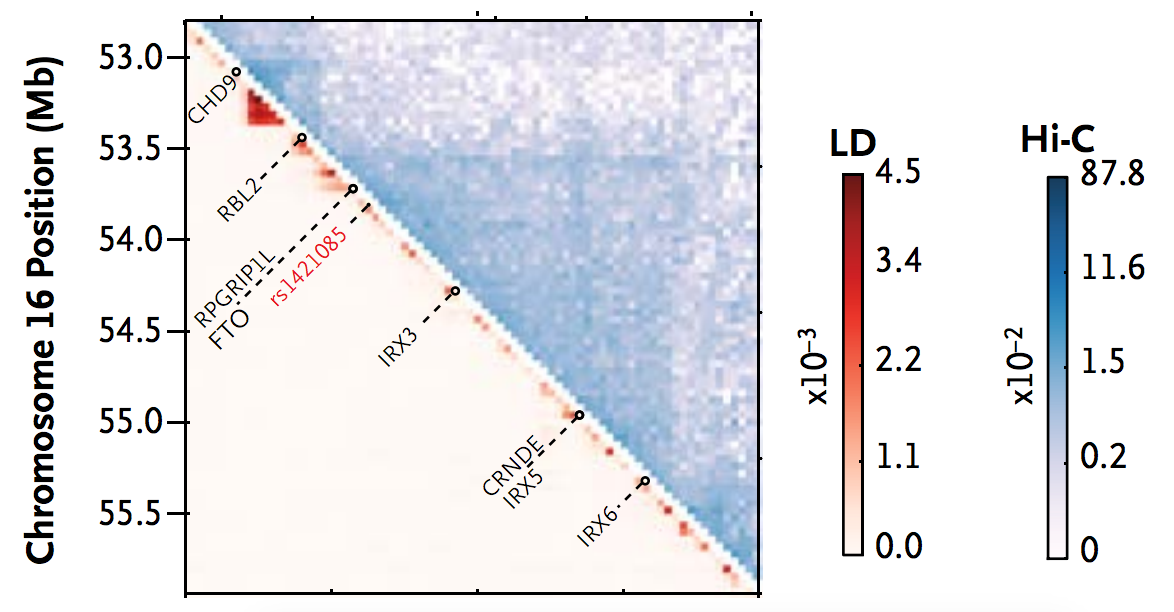

- Use Hi-C data to identify a Topologically Active Domain (TAD) around the lead GWAS SNP and find chromatin interactions with nearby genes, restricting potential causal gene set to those within the TAD.

- Identify genes with genotype-associated expression (IRX3/IRX5) from the causal set.

- Measure genomewide expression in relevant tissue from risk/non-risk allele carriers and identify differentially expressed genes. Infer targeted cellular processes based on the pathways these genes are in.

- Use PMCA method predict causal variant. In short, using weight matrices from known motif families and cross-species analysis, count the number of (a) conserved motifs; (b) multiple consecutively conserved motifs (called “modules”). Measure enrichment of motifs, motifs in modules, and modules relative to local shuffling and identify highest scoring SNP (and the motifs they disrupt).

- Multiple motifs were implicated, but ARID5B had highest expression in relevant (adipose) tissue and expression of ARID5B gene was correlated with expression of IRX3/IRX5 in controls.

Schizophrenia : MHC/C4

Sekar et al. “Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4” 2016 Nature

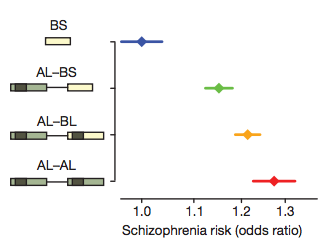

This paper looks at GWAS for schizophrenia in the complicated MHC region, identifies a relationship between copy number and expression of the C4A and C4B genes, and shows that the subsequent expression of the gene is associated with schizophrenia. Multiple biological assays are used to localize the specific neuronal tissues and mechanisms related to these genes and implicate synaptic pruning.

- Perform a large-scale GWAS. The strongest GWAS hit for schizophrenia is in the MHC, with the most significant SNPs lying near the C4 gene. There is a known association to CSMD1 (on chr8) which codes for a regulator of C4. Focus on this gene.

- Measure the copy number of each C4 gene was using molecular methods in 162 HapMap CEU samples. Identify four common structural haplotypes.

- Identify SNP haplotypes that correlate with the C4 structural haplotypes. Multiple SNP-haplotypes correlated with individual structural haplotypes (but not vice versa).

- Measure expression of five regions from 674 post-mortem brains and quantify relationship between C4 copy number and expression. RNA expression was correlated to copy number of C4 and isotypes.

- Construct genetic/structural predictors of C4A/C4B expression levels in the brain. Fit where E is expression and is the number of structural elements of type . These explain 71% and 42% of the variance in expression, more than any single cis-eQTL.

- Construct SNP predictors of C4 alleles. Use standard haplotype imputation software (BEAGLE) to predict into large individual-level GWAS data (N=65,000). Associate the imputed expression with schizophrenia as well as local SNPs.

Thoughts

My first thought is that this takes a lot of work. And that’s partially due to the fact that both GWAS SNPs were actually tagging unobserved biological mediators between genetics and expression (copy number for C4A/B and an enhancer for IRX3/5). The optimistic model where the lead GWAS SNP directly disrupts the nearest gene did not apply. Indeed one of the key findings of the Smemo et al. paper is that the target gene can lie >1MB away from the causal SNP and still interact in 3D chromatin space. Sekar et al. demonstrated how genetic prediction of expression from a small targeted study into a big GWAS helped confirm the impact of C4A/B in a way that could not have been done directly. This is an approach that myself and other groups have been thinking a lot about and I believe it’s a very powerful framework for integrating such mediators across many studies. In both instances, one link of the causal mechanism was made by looking at genes that code for relevant regulators. Sekar et al. focused on the C4 genes because they were regulated by a known schizophrenia-associated gene. Claussnitzer et al. focused on the ARID5B motif because the corresponding gene was co-expressed with IRX3/5 and associated with adipogenesis.

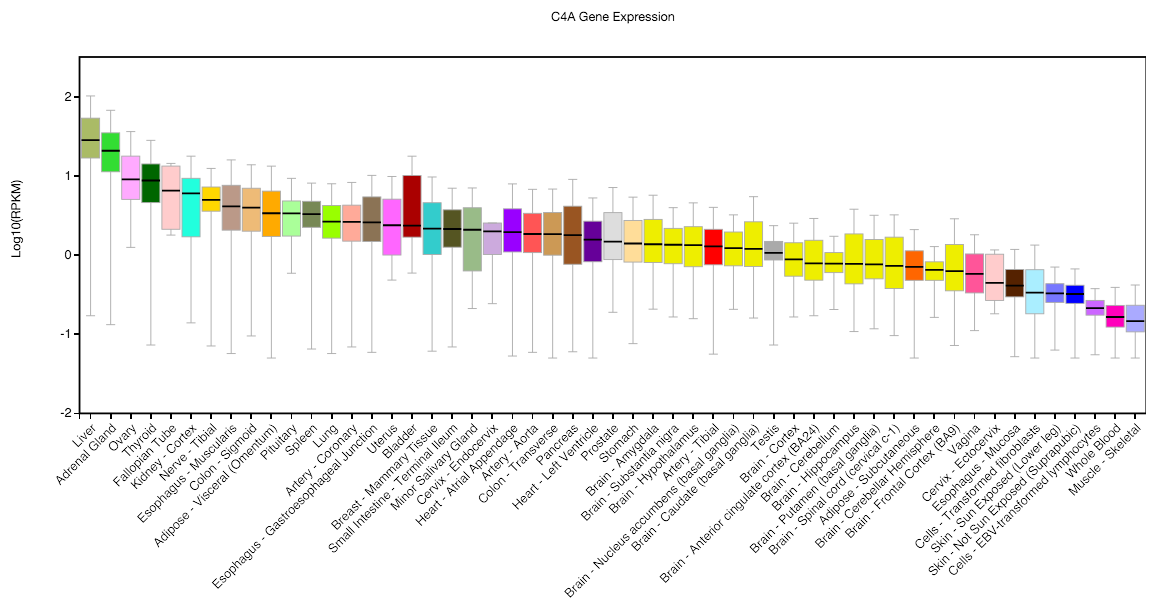

The relationship to tissue-specificity is also complicated. Using the GTEx resource (which has generously made data and analysis tools publicly available), we can see above that neither gene is blatantly specific to a relevant tissue: adipose ranks 17th for expression of IRX3, and brain ranks 29th for expression of C4A. However, both loci were validated using expression in the relevant tissue, and used absence of expression in other tissues to short-list the possible causal pathways. Simple cross-tissue comparisons did not point to a single, clearly relevant tissue. That said, finding the right tissue was crucial to understanding the underlying mechanism. In the case of C4, the regions of the brain where these effects were most active implicated synaptic pruning. Whereas in the case of IRX, a genetic effect on expression was not observed in whole-adipose tissue, but only in preadipocytes. Background cross-tissue variability appears to be high enough to mask true underlying tissue-specific effects.

As more loci are characterized in this rigorous way, it will be interesting to see if these observations continue to hold up or if other patterns emerge.